Glacial Shifts

Intercepting excess with public parks.

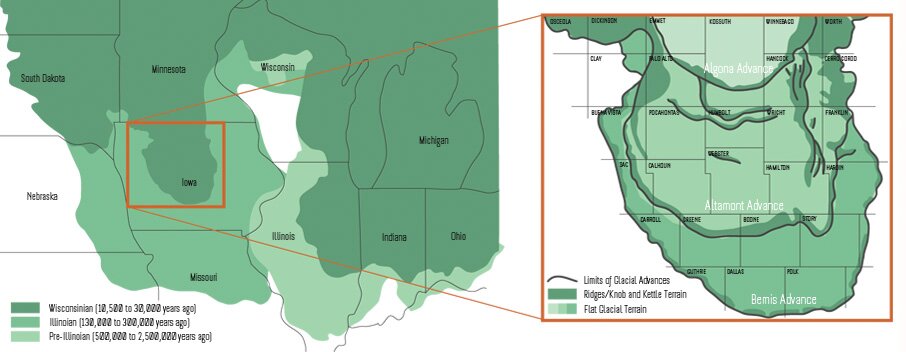

Fifteen thousand years ago, the final surge of a giant sheet of glacial ice heaved into North America. It moved at record speed, carrying rich, black sediment and leveling the land flat and easy to till. These deposits became known as the Des Moines Lobe, the southernmost tip of which is now a hill holding the state capital in the City of Des Moines.

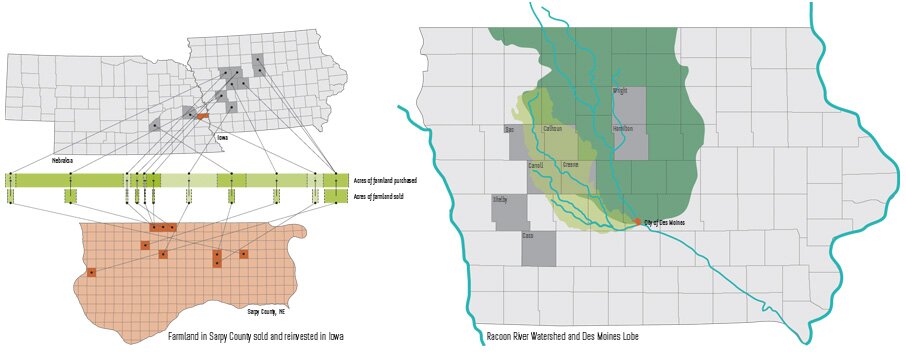

Combined with the climate, the Wisconsinian glaciation created some of the world’s best conditions for growing commodity grain crops. Through Shifting Thresholds we discovered that these conditions have attracted new investment from outside the state in recent years. A number of farms sold for urbanization in neighboring Nebraska have reinvested in farmland within the fertile Des Moines Lobe through the 1031 like-kind land exchange IRS tax code. Here, federal tax code merges urbanization and deep time.

Local farmers must produce greater yields to keep up with the rising land and rent prices, as more buyers enter the limited market. Tillable area is maximized, subsurface tiles are installed to whisk away excess rainwater as fast as possible, and GPS is employed to target nutrient fertilizer application to specific soil conditions with precision. Land productivity must meet market pressures to survive, and exceed them to thrive.

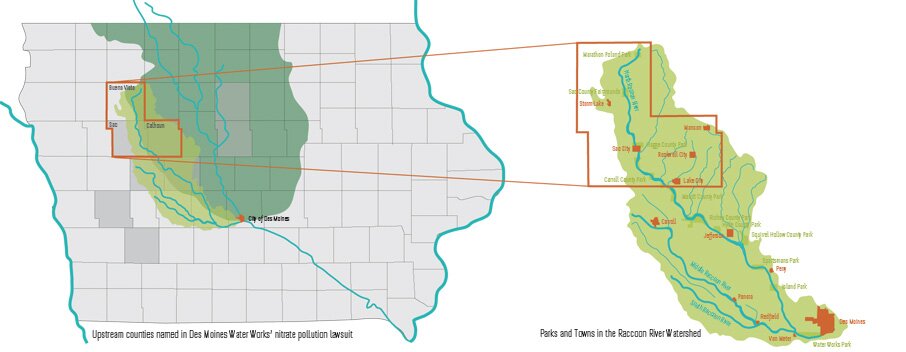

These market and technological shifts are not isolated to the farm fields. Every action made in landscape is absorbed and transmitted through water, soil, and air. The city of Des Moines draws its drinking water from the Raccoon River carving through the western edge of the Des Moines Lobe. Despite voluntary conservation efforts to reduce nutrients in waterways, Des Moines has had to increase filtration of nitrates from its water before piping to homes and businesses. In 2015, Des Moines Water Works, the entity responsible for delivering clean water to Des Moines residents, filed a lawsuit against the drainage districts of three upstream counties in the Raccoon River Watershed. A federal judge eventually dismissed Water Works’ claims, determining that drainage districts don’t have power to address them and that water quality problems are an issue for the state legislature.

Although seen as politically divisive by many, the lawsuit forced information about a public good (clean water) that tends to be underproduced by the market. There is rarely profit to be made from the production of information about public goods like clean water and air, so we must rely on forces outside the market to keep us informed. The lawsuit also underscored an important challenge in managing public goods: there is little incentive for individuals to spend personal resources on them. Why would a small number of people absorb the cost, giving everyone else a free ride?

Emerging Terrain sees a potential solution to this challenge by using a public good to protect a public good. The Raccoon River bisects eleven public parks from the top to bottom of its watershed in Des Moines. Can these parks be designed and engineered to intercept and absorb excess nitrates in the water as it travels through the watershed? Stay tuned as we find out.

.